'I Married a Jew,' 80 Years Later

An Atlantic essay published in 1939 found its modern counterpart in a much-criticized Washington Post piece published in 2018.

In a recent Washington Post opinion piece that was lambasted on social media, a writer named Carey Purcell wrote that she was done dating Jewish men after two previous relationships ended poorly. “I’ve optimistically begun interfaith relationships with an open mind twice, only to become the last woman these men dated before settling down with a nice Jewish girl,” she explains. “At almost every event I go to, [Jewish men] approach me,” she writes later in the piece. “As flattered as I am, I don’t welcome the complications and potential heartbreak I’ve experienced back into my life.”

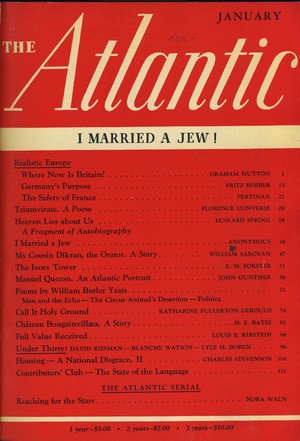

Purcell’s article—with its descriptions of her WASP-y manners and martini-making skills, its reference to the archetype of the “motorcycle-driving, leather-jacket wearing ‘bad boy,’” and its superficial handling of Jewish identity—has the feel of a personal essay from another era. And, in fact, a contributor tackled the same subject for The Atlantic almost 80 years ago, in an essay for our January 1939 issue simply and provocatively titled “I Married a Jew.” The author of that essay, whose identity was kept secret, reflects on her relationship with love and some pride, even as she delves into the religious and ethnic tensions that make it fraught.

In many ways the contributor’s story mirrors Purcell’s. Raised Christian, and identifying as Gentile, the unnamed writer fell in love with a Jew and embarked on an interfaith relationship. And like Purcell’s ex-boyfriends, the writer’s husband, Ben, is described as far less devoted to the Jewish faith than his parents. Ben “goes to synagogue on Rosh Hashana to please his mother, and during the rest of the year wavers between agnosticism and downright atheism,” the anonymous author writes. “The moment Ben is away from his family, his Jewishness drops away from him like a cloak,” she notes later in the piece.

Ben and the writer face the disapproval of their parents, just as Purcell faces that of her ex-boyfriend’s mother. At one point, the writer imagines a conversation between Ben and his Jewish mother:

“Ben,” she most likely said, “it grieves my old heart to have you marry a Shiksa rather than one of us. The old persecutions are rising again throughout the world. We have need, as never before, to stick to our own people and traditions.”

In Purcell’s telling, her boyfriend’s Jewish mother expresses a similar sentiment more bluntly when asked by her son not to contact Purcell directly on her cellphone, yelling, “If she were Jewish, she’d understand!”

Though Purcell’s piece, which comes off as tone-deaf and negligent, was published at a time when threats against Jews are on the rise, it lacks the much darker overtones that make the 1939 Atlantic piece chilling in hindsight—and that today give sickening context to the tensions surrounding the interfaith union it describes. While Purcell introduces herself by saying that “At first glance, I fulfill the stereotypes of a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP),” for instance, the Atlantic writer begins with the apparently earnest statement that her parents “are both what Mr. Hitler would be pleased to call ‘Aryan’ Germans.” (She writes in the same opening paragraph: “I frequently find myself trying to see things from the Nazis’ point of view and to find excuses for the things they do—to the dismay of our liberal-minded friends and the hurt confusion of my husband.” She also mentions that her friends sometimes refer to her, playfully, as “our little Nazi Gertrude,” possibly her real name and possibly a pseudonym.)

And while Purcell includes no cautionary words from her own family, the Atlantic contributor relates a warning issued by her German American mother:

“Married to a Jew, you will be barred from certain circles. They can say what they like about Germany, but democratic America is far from wholeheartedly accepting the Jews. Remember that Ben couldn’t join a fraternity at his university. Remember there are clubs and resorts and residential districts that bar Jews. Remember there are a dozen other less tangible discriminations against them.”

There are other alarming details. When Ben and the writer discuss their respective families’ faiths, they discuss Judaism not only as a separate religion but as a racial identity deeply ingrained in Jews living around the world which serves as the root of a global “problem.” “Ben is ready to discuss the separate differences between Jews and Christians,” the author writes,

but when I lump them all together as constituting the world’s Jewish problem he flares up. Oh, there’s a problem all right, he allows, but it concerns only the Jews, and he’d thank the Gentiles to mind their own business and keep their hands off. To which I reply, “How can we ignore it when it concerns us as much as the Jews? How can the host ignore the quarrels of the guest in his house?” To which Ben answers with some heat; “We are not guests; we are good citizens of the countries in which we live.”

Written on the eve of World War II, when the Holocaust was already underway, this Atlantic piece serves as a lasting record of the tension between Gentiles and Jews that festered in the United States—a tension that not only threatened romantic relationships but that drove real prejudice and real discrimination. And it did not end with the war, or the Holocaust: When, for example, my Protestant-raised grandmother married my Jewish grandfather in 1956, his parents sat shivah for him—treating his choice to marry outside of the faith as akin to his death. Meanwhile, her father offered his resignation at work.

From the midst of that anti-Semitic history, the Atlantic contributor optimistically concluded,

When one of my husband-hunting girl friends asks me, “Do the Jews make good husbands?” I think of Ben, respecter of women, generous to a fault, kind to every creature, open-minded, witty, sober of habit but gay of manner, imaginative and ambitious, and say with all my heart, “The best in the world!”

“I seldom think of Ben as being Jewish and he seldom thinks of me as a Gentile. We are just Ben and Gertrude to each other,” she writes. “It is that way when you love.” And Purcell? She’s “tired of being a Jewish man’s rebellion.” Writing 80 years apart, she and the Atlantic writer came to different conclusions, but neither could transcend the same old imagined dichotomy.