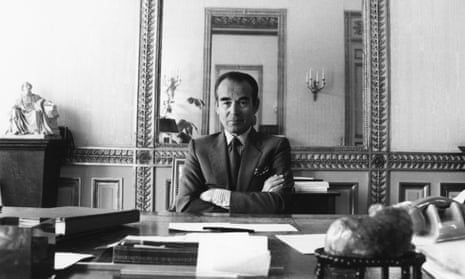

The lawyer and politician Robert Badinter, who has died aged 95, became the conscience of his country when he persuaded France to abandon the death penalty, against fierce opposition, in 1981.

Although he had many other roles in a life devoted to justice, combating oppression and upholding the rule of law, Badinter, a socialist and humanist, will be remembered for his part in abolishing capital punishment, one of his first acts as French justice minister under the socialist president François Mitterrand, a post he held until 1986.

Badinter began his career in Paris in the early 1950s, under the tutelage of a charismatic lawyer, Henry Torrès, who told him: “You defend a man who has killed or stolen because they are first of all a man.” It was a lesson Badinter took to heart, and he represented not only celebrities such as Coco Chanel, Charlie Chaplin, Brigitte Bardot and Raquel Welch, but also Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the former Pakistan prime minister, as well as notorious criminals and a convicted child murderer who was among five people he defended who were sentenced to death.

In his book The Execution, published in 1973, Badinter recalled watching the killing of a man he had represented, and described the “sharp snap” of the guillotine blade. It was an experience that left him with the profound conviction that state-sanctioned murder was wrong. Becoming what some called the “assassins’ lawyer” had its risks: in 1976, a bomb exploded on the doorstep of the family’s Paris apartment. “To defend is to like defending, not to like those one is defending,” he once said.

In 1981, as the new justice minister, he presented the law removing the death penalty and pushed it through parliament, earning the nickname “Monsieur Abolition”.

Although a few French intellectuals, philosophers, legal minds and politicians had raised the idea of abolishing the death penalty since the 18th century, until Mitterrand came to power in May 1981 there was no serious attempt to do so. Postwar France had been run by conservative right-wing governments that supported capital punishment; polls in 1980-81 suggested there was no public appetite for abolition either, with 63% of French approving of the death penalty, which was then carried out by guillotine.

The socialist president, however, had made it one of his campaign promises and the bill, consisting of nine short articles, was one of the first introduced to parliament.

It was adopted by the lower house, the national assembly – where the left had a massive majority – by 363 votes for, 113 against, and five abstentions, after an impassioned and fiery speech by Badinter. After a heated three-day debate in the upper house, the senate, it was passed by 160 votes to 126 and adopted without a second reading, becoming law in October that year.

“Tomorrow, thanks to you, France’s justice will no longer be a justice that kills,” Badinter told MPs.

He also enacted Mitterrand’s election promise to decriminalise homosexual relations between those aged over 15 years, the same as for heterosexuals, and ended the “special” military courts that operated outside the regular legal system. He attempted to improve conditions in French prisons, frequently criticised in national and European reports, but with limited success; and gave ordinary French citizens direct recourse to the European court of human rights.

Badinter was born in Paris, the son of Simon Badinter, a commercial engineer and fur trader and Charlotte (nee Rosenberg), both from Jewish families from Bessarabia in eastern Europe, an area which is now part of Moldova and Ukraine. They had arrived in France in 1919 to escape the pogroms and the Bolsheviks, and met at an exiles’ ball in Paris.

Until the German invasion of France in 1940, the family basked in the freedom the country offered. In 1942, Robert’s beloved maternal grandmother Idiss, who had taught him Yiddish, was arrested and died while being deported to Auschwitz. The family moved south seeking refuge in Lyon, then a “free zone” administered by the collaborationist government of Marshal Philippe Pétain.

On 9 February 1943, Robert returned home to find the Gestapo in the family apartment. Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo leader known as the “Butcher of Lyon”, had ordered that Jews in the city should be rounded up and deported. Simon was arrested and sent to the Sobibór extermination camp, where he died. Several other family members were murdered by the Germans. Issued with false identity papers, Robert, his mother, and his elder brother, Claude, found refuge in Chambéry in the French Alps until the end of the second world war.

After the liberation, Badinter studied law and literature at university in Paris and at Columbia University in New York.

He later taught law at universities in Dijon, Besançon and Amiens, and at the Sorbonne in Paris, but turned to politics, and in 1981 he began his government career.

In 1986, Mitterrand appointed Badinter president of the country’s constitutional council, where he remained until 1995 when he became a senator in the upper house of parliament, sitting there until 2011. At an international level, he presided over the Badinter commission that arbitrated for a settlement in the former Yugoslavia. He also helped draw up the Romanian constitution in 1991 after the fall of the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu.

In her 2009 biography of Badinter, the writer Pauline Dreyfus described him as a “contemporary legend”. “The coherence of his convictions is striking,” she wrote. “Like his alter ego on the right, Simone Veil, [Badinter] embodies a form of unquestionable moral authority and integrity.”

The French president Emmanuel Macron described him as a “a wise man above and beyond the call of duty, always helping to shed light on the most difficult decisions”.

Badinter wrote numerous books, reference and fiction, an opera script, a biography of his grandmother, for which he won a literary prize, and plays, including one on the trial of Oscar Wilde.

He remained politically engaged to the last. In 2023 he co-authored the book Vladimir Putin: The Accusation, and stressed the importance of standing up to and defeating the Russian leader. “I don’t think we French realise enough that there is a war going on in Europe today, two hours by plane from Paris”, he told French radio. “We forget. I’ve been to war, I know what war is, and it exists, it’s there.”

He is survived by his second wife, Élisabeth (nee Bleustein-Blanchet), a writer, philosopher and feminist, whom he married in 1966, and their children, Judith, Simon Marcel and Benjamin. His first marriage, in 1957, to the actor Édith Vignaud, known by the stage name Anne Vernon, ended in divorce.